The Nature

Observer’s Journal

The Nature

Observer’s Journal

The Many Faces of Black Vultures

Chuck Tague

When I think of Black Vultures in Pennsylvania, I picture a squadron of large, dark birds cruising high over the Allegheny Front. Their tight formation resembles a squad of fighter planes, very different from the ragtag bands of Turkey Vultures that diddy-bop over the treetops. The smooth glide and precise spacing tell me they’re Black Vultures long before I see their silvery primaries, bulky heads or keystone silhouettes.

Since most western Pennsylvania sightings are from remote outcroppings along the Allegheny Front, I regarded Black Vultures, along with ravens and Golden Eagles, as aloof residents of our state’s rugged, mountainous areas.

Now I live in Florida. When I drive from my old state to my new one, if I’m lucky, I spot some of the Black Vultures that ride the high ridges in West Virginia and Virginia. However, it’s not until I near the South Carolina/Georgia line and the first of the Sabal Palms that I find Black Vultures in good numbers. Southern sunshine, Black Vultures and Sabal Palms conjure up a very different image. I imagine the vulture roost at Lake Woodruff.

Lake Woodruff is a National Wildlife Refuge in Deleon Springs, Florida, west of Daytona. Each winter over ten thousand Black Vultures gather there. I always try to get to Lake Woodruff before the vulture activity starts but there’s no pressure to beat the sun. Eight o’clock is early enough. The mist is still burning off the marshy impoundments.

A vulture kettle

They rise up on morning thermals like bubbles in a tea kettle

As I walk along the levies looking for rails, sparrows, Limpkins or waterfowl, gangs of Black Vultures block my path. Sometimes there are over a hundred loafing on the dikes. Some fly off, others hop or run ahead and wait for me to again get too close. There’s something about a Black Vulture’s gait that borders on silly and I can’t help but laugh. A group of six or ten always finds a birder good company, or at least momentarily fascinating. They amble along two or three steps ahead like puppies; big, feathered puppies that smell like vomit. They also make a strange little “gruff, gruff” bark.

WQED Pittsburgh’s Bird Blogger Kate St.John (AKA Dances with Vultures)

When the morning thermals rise, maybe about nine or nine-thirty, a test flight lifts off. If the air is too cool the vultures struggle a bit, then circle around as if to show the others, “Yeah, that’s what I thought”. Then they settle back in the palm hammocks. If the thermals have lift, others join them. Soon the sky darkens with thousands of birds. The exodus lasts over an hour. For the rest of the morning flocks come and go.

The “Audubon Lookout” at Lake Woodruff NWR is favorite gathering spot for Black Vultures.

Halfway around the first impoundment is an observation deck donated by the local (West Volusia) Audubon Society. It’s an elaborate structure, two stories high with steps, railings, spotting scopes and a peaked roof. Layers of whitewash obscure the original color. The vultures appreciate the gift; the local birders feel betrayed.

To me Florida vultures and their Pennsylvania counterparts are as different as a misty Florida morning and a blustery afternoon on the Allegheny escarpment. It’s hard to believe these vultures are the same species. Neither impression, however, jives with my recollection of Black Vultures in the Amazon River town of Iquitos, Peru.

As our bus wound through the narrow streets, past tin roof shanties, thatched huts and old stone buildings, Black Vultures were everywhere, more numerous than pigeons in Downtown Pittsburgh or Laughing Gulls on a Florida beach in winter. The vultures perched on the peak of every roof, on top of every pole and trash bin like gruesome gargoyles; like hunched-over, darkly comic harbingers of death.

Black Vultures – tough inhabitants of the wild Alleghenies, friendly clowns of Sabal Palm hammocks, grim reapers patiently watching over squalid jungle villages –- “Will the real Black Vulture please stand up?”

I did some research and gained much insight into the Florida and Peruvian Black Vultures.

Communal roosts, like Lake Woodruff, are crucial to Black Vultures’ foraging success. It’s there birds exchange information about the location of carcasses, garbage and other feasts. Vulture roosts have two requirements but sites that meet these are becoming difficult to find. There must be sufficient perches. Trees are preferred but a two-story observation tower will do. A roost also needs a minimum of human disturbance during roosting hours.

In eastern Pennsylvania, Black and Turkey Vultures gather at Gettysburg National Battlefield. In western Pennsylvania, Turkey Vultures roost at the Wildflower Reserve at Raccoon State Park and near Davis Hollow at Moraine State Park. What do these have in common with Lake Woodruff? They all have gates with signs that read, “Closed at Sundown”.

In the American tropics Black Vultures cannot compete with other scavengers, especially in dense forests. They’re forced into a different lifestyle, and they’re well-adapted for this niche. In towns without proper sanitation, where garbage is thrown into dumps or left on the street, Black Vultures are the cleanup crew.

My readings, however, just compounded the puzzle of Black Vultures on the Allegheny Front. The sources all agree that Black Vultures are non-migratory, “or nearly so” and prefer open habitats without a dense canopy. Birds of North America Online boldly states, “Black Vultures avoid higher elevations of Ozarks and Appalachians and are most abundant in flat lowlands, such as coastal plains.” Huh? That’s not right. All of Pennsylvania’s hawk watchers can’t be mistaken.

Could it be that although I stood on the rim of the Allegheny Front, the Black Vultures I watched were soaring over and surveying the agricultural valley a thousand feet below? Is the mountain only a convenient obstruction to the Black Vultures that lifts them to a lofty view of their domain? Black Vultures are efficient soaring birds that roam great distances in search of carrion. Is the ridge not a migration route at all but an expressway around their huge home range?

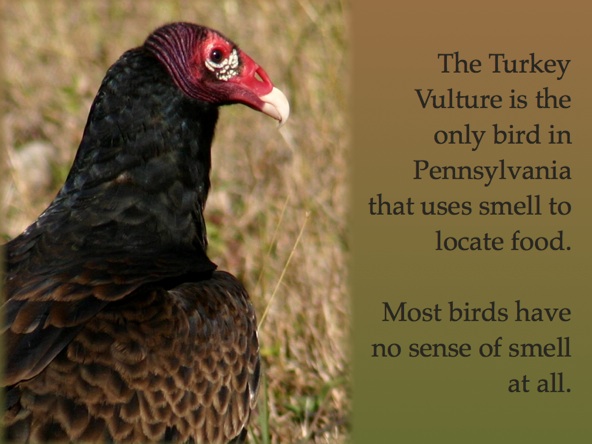

Unlike Turkey Vultures that use a sense of smell to find carrion, the Black Vultures use visual clues, especially the movements of Turkey Vultures. Could it be that the Allegheny Front Black Vultures do what Black Vultures do across North and South America? Do they shadow the Turkey Vultures that migrate along the ridge?

Maybe I was right all along and Black Vultures do inhabit the eastern edge of the Alleghenies? Throughout their range they breed in caves, abandoned buildings and dense secluded woods. Could the steep, rocky escarpments provide nest sites to complement valleys that are rich in road kill and agricultural waste?

Neither my newly acquired insight into these high-soaring, keen-eyed scavengers, nor the mystery of their movement along the Allegheny Front, has diminished my admiration of Black Vultures. Although they’re not ideally suited for rugged mountains or dense rain forests they get by with another quality; they are quick to adapt to and take advantage of people’s endless changes to the environment. Whether it’s agricultural practices in eastern United States, urban sprawl in central Florida or human expansion along South American rivers, Black Vultures are there to exploit new opportunities.

Vulture factoid: How do Black and Turkey Vultures keep cool in the hot American tropics? They have many cooling strategies but in extremely warm weather vultures perform urohidrosis, or defecate on their legs, to reduce their body temperature. The evaporation removes body heat but leaves a calciferous coating.

Tuesday, September 27, 2011